Part 11: Al Andalus

Chapter 11 – Al Andalus – 1200 to 1212With the twelfth century drawing to a close, the House of Jizrunid emerges a transformed power, with this family of wanderers and fighters rising to become the last Muslim holdout in Iberia.

The Jizrunid rulers of Cádiz have all been men of war, thus far, and Emir Galind is no different. None of the previous emirs and sheikhs were anywhere near as successful as Galind, however, not even close. Galind alone can lay claim to defeating the great Christian Alliance, Galind alone is revered as one of the greatest strategic minds of his age, Galind alone is known in history and legend as the Kingkiller - and for good reason.

As the thirteenth century dawns, however, Emir Galind comes to the realisation that he is not the man he once was. His mind was as astute and sharp as ever, but his pegled ached constantly, his reflexes were slowing, his belly was fattening and his swordplay was quickly declining.

The years had flown past, and before he knew it, Galind was an old man. He still had a responsibility and a duty, however, and upon his return to Cádiz he began settling back into ruling his emirate once again.

His victories on the battlefield had made Galind nigh untouchable, and he used this hard-earned influence to continue centralising the Emirate, demanding greater contributions and tithes and manpower from his vassals. He also drafted laws that allowed him to freely revoke titles from heretics and heathens, with his eyes still set on further expansion.

In the north, an agreement was reached between the two most powerful Christian kingdoms of Iberia, Aragon and Portugal. The alliance binding Aragon, Castile and Navarre had been shattered by Galind, with the Emir also dealing a humiliating defeat to the Portuguese, so these two powers decided to forge a new pact against Cádiz, solidifying this newfound alliance with marriage pacts.

An important development, but Emir Galind was focusing on his own emirate, trying to increase his influence amongst the aristocrats. He was planning something elaborate, though not many knew exactly what it was, and he would need the support of his vassals to succeed. To that end, he visited the estates of his vassals, he awarded vizier positions and important assignments to the more powerful nobles, and financed the construction of several mosques and shrines to increase his popularity amongst the poor.

For perhaps the first time in his life, Galind took a dominating role in actually ruling over his vast territories, as opposed to just conquering some more. Within a few years, he managed to attract merchants and traders from all across the Muslim World to Cádiz, turning his small city of fisherfolk and farmers into a thriving centre of trade.

Unfortunately, whilst Emir Galind was busy meddling with accounts and legal dispositions in Cádiz, trouble was brewing just beyond his borders. With financial support from Aragon, a Catholic peasant managed to build a huge army around himself, vowing to overthrow the ruling Muslim class.

He and his 20,000-strong force set off on a march southward, fired up with the belief that Christ walked alongside them. Emir Galind initially dismissed the invading force as a few riled up peasants, but these peasants somehow sacked Granada whilst on the march towards Cádiz, capturing one of the most powerful fortresses in the Emirate.

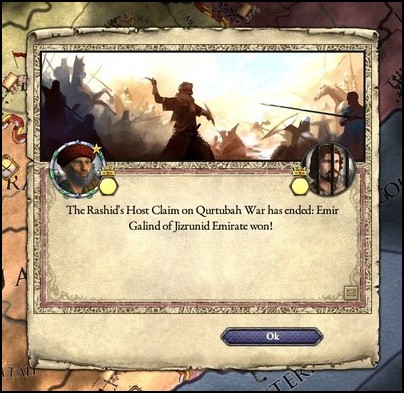

Suddenly realising that these peasants posed a legitimate risk, Emir Galind raised his troops and sent them to meet the invaders, commanding the army from a distance. The Christians didn’t need much prompting, they immediately rushed to attack the numerically inferior Cádizian army upon its arrival, sure that victory was theirs.

One would think that Galind’s reputation would be enough to ward off any overconfidence in his enemies, but apparently not, and through precise flanking manoeuvres and perfectly-timed reinforcements, the peasant army was destroyed.

Emir Galind sent the army ahead whilst he returned to Cádiz, leaving the rebels to be crushed in another battle, in which the peasant leader was captured and imprisoned. With that, the revolt came to an end, though Rashid’s suffering was only beginning.

Whilst Galind busied himself with executing the overeager peasant commanders, the Christian kingdoms to the north had been busy, with Portugal, Castille and Aragon all attacking the pitiful Aftasid Sultanate and leaving it with almost nothing.

Galind was, if anything, an opportunist, and this was certainly an opportunity. This new Christian alliance was far too powerful to attack, he would have to wait for trouble to brew within their ranks before striking, but the Aftasid Sultanate was already on the verge of collapsing...

Under the pretence of ‘protecting against the heathens’, Galind authorised a raid into Aftasid territory and captured the city of Shlib, the last piece of land they held in the south.

The victory, however anticlimactic, was still important in that it left the Jizrunids as the unrivalled Muslim power of Iberia.

With that, Galind’s finally felt confident enough to reveal his ultimate ambition, with the Emir crowning himself the "Sultan of Al Andalus" in a costly, extravagant ceremony. And in a ritual that would quickly become tradition, Galind raised a sword to the heavens whilst a shimmering gold cloak was clasped to his shoulders, with his assembled vassals bowing their heads and proclaiming him Sultan.

If Galind was actually going to be recognised as the ruler of a revived Al Andalus, however, he had to earn the support of the North African Berbers. Galind’s viziers had already been in Morocco and Tunis for years by then, subtly improving relations between Cádiz and the Berbers, and it was only now that these efforts bore fruit.

And the Sultan of Morocco and Emir of Tunis both agreed to recognise Galind as the heir to the Umayyads, in return for marriage pacts and alliances.

Reviving a title that had been lost for almost two hundred years cannot go without celebration, and after his widely-publicised coronation came to an end, Galind announced the beginning of several weeks of festivity. Rich foods and expensive wines littered the many palaces of Cádiz, the nobles engaged in all the debauchery and hedonism they usually preferred to hide, and the smallfolk were just happy to get a few days off.

And with that, Galind has become the first Jizrunid Sultan of Al Andalus, fulfilling an ambition that spanned 140 years worth of conquest and diplomacy, uniting the warring Taifas and reviving the legacy of Córdoba.

It would not be the same, however, Galind was determined to create something else. This Al Andalus, his Al Andalus, would continue pushing back the Christians, it would become the centre of intellectual and scholarly learning, it would spreads its shadows across seas and continents, it would become a power feared even in the far-off reaches of Tenochtitlan and Beijing. From the once-insignificant city of Cádiz, all the world would bend the knee.

And he, Galind the King-killer, was its founder.

The newly-crowned Sultan Galind would not live for much longer, unfortunately. He had lived to the respectable age of 67, and it was sheer ambition that had driven him for all those long years, suffering through the lows and relishing the highs. He had warred and he had murdered, he had schemed and he had plotted, he had drunk and he had loved, he had lived a life that would be remembered for centuries.

He now leaves his young kingdom in the hands of his only living son – Fath. The new Sultan knows full well that Galind’s vision of an Iberia united under Jizrunid rule will not be easy to achieve, perhaps it might even be impossible, but not for lack of trying.

Just days before Galind’s death, the King of Portugal inherited the Duchy of Castille, before integrating his two realms under the re-created Kingdom of Castille. That puts all of Christian Iberia in a powerful alliance, united by their hatred of the Jizrunid Muslims, and determined to reconquer their lost territories.

All of these seemingly age-spanning conflicts are mere squabbles compared to what is happening in other parts of the world, however. After all, who cares for the return of Al-Andalus, when a rapidly expanding empire spanning thousands of miles is on the rise in the east? Who cares for the war between Christian and Muslim, when a pagan threatens to destroy them both? Who cares for Galind’s dream of uniting Iberia, when there is a horselord who dreams of uniting the whole world?

The Mongols have arrived.